Whether you're a public company, private business or nonprofit, an audit provides a crucial independent evaluation of your financial statements that ensures adherence to accounting standards while building trust with your stakeholders.

Table of Contents

The purpose of a financial audit is to provide independent assurance that your company’s financial statements present a “true and fair” picture of your financial performance and position. Publicly held companies are required by the SEC to provide audited financial statements that are free from material error. Similarly, banks and potential buyers may also require audited financial statements as proof that your business is financially sound, and the increased confidence an audit provides can often improve a company’s relationships with business partners.

Many nonprofits choose to perform an independent audit occasionally to ensure sound financial practices. State or federal agencies may also require nonprofit organizations to undergo an annual audit as a condition of funding. These mandated audits for nonprofits are known as a ‘single audit’ which allows the organization to meet audit requirements set by many different funding organizations and agencies.

Internally, an audit can help put meaning behind your company's financial numbers. Financial statement footnotes can help to explain financial data and make that information usable and relevant to non-financial members of your organization. For nonprofits, reporting and audit documents are a chance to communicate a compelling financial story that inspires giving and donor confidence. In both single audits and financial statement audits, the reporting process can also identify opportunities for improving internal processes for greater efficiency and accuracy.

Now that your audit is on the horizon, you’ll want to do some up-front preparation and planning to make sure that the process goes smoothly.

Schedule a planning meeting with the audit partner and manager well in advance of the engagement fieldwork. Work collectively to identify and vet out potential issues and roadblocks that could cause delays and develop a game plan. Engagements that are not properly planned with partner/manager involvement often go sideways and have an increased chance of running inefficiently.

Having auditors in your office asking questions and requesting documentation can be a stressful experience. Help your employees prepare by assigning roles and a point person for each of the audit areas. If your employees (and the auditors) know who to turn to when they have a question, it will make the process more effective.

If you don’t already have your internal processes and controls documented, now’s the time to do so. Auditors are required to document their understanding of your control environment, and you and your employees are experts on that subject.

Consider compiling the following process and control documents:

Your auditors will be requesting a lot of information during the process, and you want to be able to provide that information easily by having a complete set of records before the audit begins. You’ll want to make sure your reconciliations and financial statements are up to date, and your transactional records are organized so you can quickly provide them to the auditors for their sample selections. Additionally, you’ll want to gather organizational documents, contracts and lease agreements, and make sure you’ve documented any items or transactions that are unusual, especially if they are large ones.

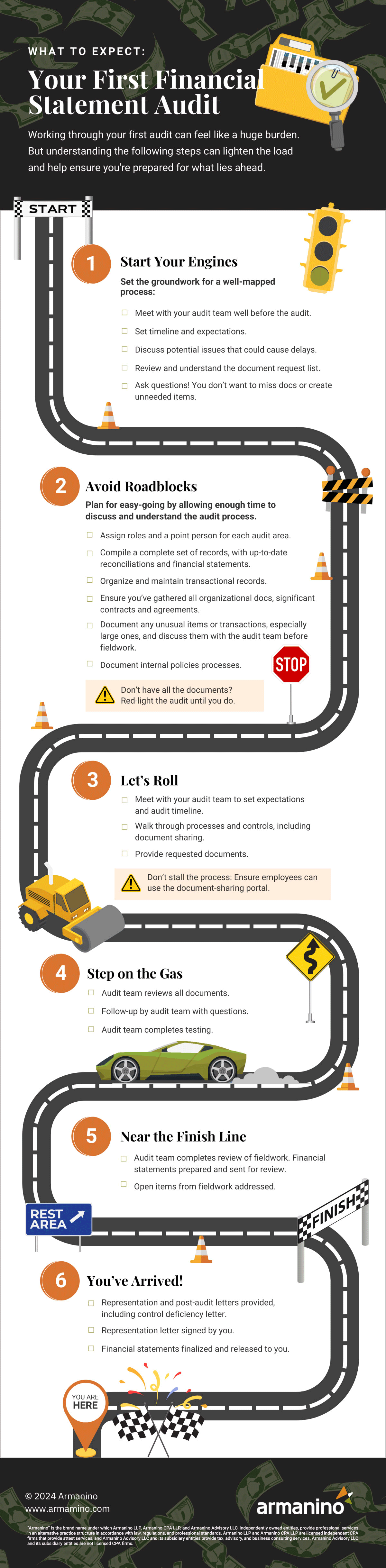

A first-time audit is a lot of work and can take longer than those that follow; there’s no avoiding that fact. But by choosing the right audit partner, asking the right questions and being proactively prepared, you can make sure the process is efficient and effective. The following infographic provides some key action items regarding what to expect on your first financial audit:

Want to display this infographic on your site? Copy and paste the following code. Be sure to include attribution to armanino.com with this graphic.

Government grants can be a great source of funding for nonprofits. These grants boost the credibility of the organization, provide funding for the organization’s programs and are not expected to be repaid. However, government grants may also require the organization to adhere to rigorous reporting and compliance requirements. One such requirement is the single audit.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, many organizations (nonprofits as well as for-profit businesses) that received federal funding through the CARES Act and other legislation became subject to the single audit for the first time. Whether you are newly subject to these requirements or your organization itself is new, these FAQs can help you prepare for your first single audit.

You will need a single audit if your organization expends $750,000 or more in federal funds during the fiscal year. The basis for determining when federal funds are expended is based on the type of federal award. For most awards, the funding is determined to be expended when the expenditure or expense transaction occurs. However, federal “expenditures” may also include pandemic-related loan programs and lost revenues as allowed by certain programs.

Determining whether an award is considered federal and subject to the single audit can be tricky. Federal financial assistance can come directly from a federal agency or be passed through the state, county, another nonprofit or other pass-through entities. If you receive funding that resembles federal assistance, you should confirm with the funding agency whether the award is considered federal.

In addition to the audit of your regular financial statements, your auditor will also perform a compliance audit in accordance with the Uniform Guidance (UG). The UG is a set of rules and regulations that define the administration of federal awards, including how federal funds can be spent and tracked within the financial records. The audit will focus on the testing of compliance and internal controls over compliance as they relate to your federal awards. Each federal award has unique compliance requirements. Also, be prepared to provide supporting documentation for costs that have been or will be reimbursed through federal awards.

Your auditor is required to test internal controls over compliance during the single audit. As such, it is important that you establish and maintain effective internal controls that provide reasonable assurance that you are managing your federal awards in compliance with federal statutes, regulations and the terms and conditions of the federal awards. Controls need to be documented. You may also need to add layers of review and signoffs that were not previously implemented. Refer to the Compliance Supplement, Part 6, Internal Control for additional guidance on controls.

After completion of the audit, you will need to prepare your portion of the data collection form and submit the form and audited financial statements to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse within the earlier of nine months after your year-end or 30 days after you receive the audited financial statements.

Only auditors meeting certain qualifications are allowed to perform a single audit. The Government Audit Quality Center (GAQC) recommends you consider the following factors when hiring an auditor:

Planning and communication with your auditor is key to a successful single audit. Meet with your auditor early and often to discuss the single audit plan. Ask your auditor to provide an overview of the single audit and the areas of compliance that will be tested. Identify and address problem areas in advance. Also, it is important that your schedule of expenditures of federal awards (SEFA) is complete and accurate. In response to the pandemic, the government has introduced an unprecedented amount of new government assistance programs. So having a complete and accurate inventory of your federal awards is critical for the preparation of the SEFA.

Armanino has created a high-level overview of certain elements of the Uniform Guidance to help you learn more. You can also review the full UG. It is especially important to be familiar with Subpart E of the UG, which covers cost principles, as those will be tested in almost every single audit. You should also review the applicable sections of the Compliance Supplement, as your organization is expected to follow its requirements. The nonprofit consultants at Armanino can help your organization identify, understand and comply with the audit requirements that apply to your organization.

In November 2017, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) published an updated audit and accounting guide on analytical procedures. The use of audit analytics can help during the planning and review stages of the audit, but analytics can have an even bigger impact when these procedures are used to supplement substantive testing during fieldwork. Here’s how auditors use analytical procedures to make your audit more efficient and effective—and why it’s critical for you to tell your auditor about major changes during the accounting period.

The AICPA’s auditing standards define analytical procedures as: “evaluations of financial information through analysis of plausible relationships among both financial and nonfinancial data. Analytical procedures also encompass such investigation, as is necessary, of identified fluctuations or relationships that are inconsistent with other relevant information or that differ from expected values by a significant amount.”

Examples of analytical tests include:

Auditors use analytics to understand or test financial statement relationships or balances. Significant fluctuations or relationships that are materially inconsistent with other relevant information or that differ from expected values require additional investigation.

Experienced auditors use analytical procedures in all stages of the audit. For example, analytical procedures may help the auditor during the planning stage to determine the nature, timing and extent of auditing procedures that will be used to obtain audit evidence for specific account balances or classes of transactions.

Analytics also come into play at the end of the audit. Before delivering financial statements to the company being audited, auditors evaluate whether the overall financial statement presentation appears reasonable in light of financial and nonfinancial data.

During fieldwork, auditors can use analytical procedures to obtain evidence, sometimes in combination with other substantive testing procedures, to identify misstatements in account balances. This can help reduce the risk that misstatements will remain undetected. Analytical procedures are often more efficient than traditional, manual audit testing procedures, which tend to require the company being audited to produce significant paperwork. Traditional procedures also typically require substantial time to verify account balances and transactions.

When using analytical procedures, it’s critical for the auditor to establish a threshold that can be accepted without further investigation. This threshold is influenced primarily by the concept of materiality and the desired level of assurance. The threshold is typically lower when using analytics to perform substantive testing (where the risk of material misstatement is higher) than when using analytics in planning or final review.

Establishing the threshold for analytical procedures is a matter of the auditor’s professional judgment. The threshold should factor in the possibility that a combination of misstatements could aggregate to an unacceptable amount. For example, when analyzing expense accounts, an auditor may decide that it’s necessary to investigate the difference between what’s expected and what’s reported only if it exceeds the auditor’s expectation by 10% and/or $10,000. These amounts may vary from company to company and from year to year.

When performing analytical procedures, auditors generally follow this four-step process:

For differences that are due to misstatement (rather than a plausible explanation), the auditor must decide whether the misstatement is material (individually or in the aggregate). Material misstatements typically require adjustments to the amount reported and may also necessitate additional audit procedures to determine the scope of the misstatement.

The company being audited is likely to notice when an analytical procedure unearths a major difference between expected and reported results. How? First, the auditor will ask management to explain the discrepancy. Then the auditor might ask for supporting evidence to corroborate management’s response. In some cases, the auditor will conduct more in-depth testing than in previous years when analytical procedures reveal a major discrepancy.

Analytical procedures can help make your audit less time-consuming, less expensive and more effective at detecting errors and omissions. You can help by notifying your auditor about major changes to your operations or accounting methods during the year, as well as any significant alterations in market conditions. When you understand the role analytical procedures play in an audit, you can anticipate audit inquiries, prepare explanations and compile supporting documents before fieldwork starts.

If this is your first-time audit, keep in mind that when looking for an audit firm, you should be looking for a partner with whom you can have a long, successful relationship. The first step in selecting a potential audit partner is asking the right questions. Be sure you are satisfied with the answers to the below before engaging an audit firm’s services:

Whether it’s a single audit for your nonprofit or an independent audit for your business, there’s no getting around it: the audit experience can feel stressful and confusing. Choosing the right auditor makes a huge difference, as can knowing what to expect and how to prepare. You can count on Armanino to ease the process. Learn how our Financial Statement Audit experts can help you get the most value and least disruption from your next audit — or your first.

Our seasoned audit experts can help you streamline your audit experience and strengthen your financials. Contact us today for a free scoping call to assess your needs.